Cool Creatures | Ticks

Ticks are among the most detested creatures in all of nature—but what happens when we look closer?

Image used under license from Shutterstock.com

Ticks are among the most detested creatures in all of nature—but what happens when we look closer?

Description

Ticks are among the most detested creatures in all of nature—but what happens when we look closer? In this Cool Creatures episode, Colin follows Calvin University professor Will Miller and some of his students into the field as they study ticks and the diseases they carry. As we explore ticks we find ourselves asking questions about public health, parasitism, and theology. Are ticks only dangerous pests or can they also open our eyes to the complexity and beauty of creation?

Theme song and credits music by Breakmaster Cylinder. Other music in this episode by Evan MacDonald, Pavel Yudin, Nathan King, Cosmo Lawson, Vesper Tapes, Ricky Bombino & Elizabells, courtesy of Shutterstock, Inc.

- Originally aired on September 18, 2025

- WithColin HoogerwerfandJim Stump

Transcript

Stump:

Welcome to Language of God. I’m Jim Stump

Hoogerwerf:

And I’m Colin Hoogerwerf. Today we’re bringing you another episode in a series we’ve been calling Cool Creatures.

[outside noises: “If it’s alright, we can all climb in this car and go down to the trailhead.” Sound of car starting]

Hoogerwerf:

Earlier this summer I had a chance to follow along on some field research with a professor at Calvin University and three students in a summer research program

[doors close, distant talking about starting sampling]

Hoogerwerf:

They were going out to study the creature for our episode…the tick.

Stump:

Hmm. Seems like we might have to think about a new name for the series. Cringeworthy creatures? Cursed creatures?

Hoogerwerf:

Yeah. I anticipated that. [Jim chuckles] In fact, it’s one of the reasons I thought it might be a good candidate for an episode. I’ll admit that I do tend to like bugs and insects, but even I have a hard time getting over the disgust factor for ticks. And I think that’s interesting and worth exploring. I don’t think the goal here is to try and convince everyone that ticks would make a good household pet but I wonder if it’s worth at least considering ticks as having a worthy place within the creation. Maybe even more than that. Could we learn to see ticks as interesting, study-worthy, maybe even beautiful?

Stump:

I’ll try to remain open to that possibility, but suspect that most of us will have a pretty high bar you’ll need to get over, and this one is mostly on you.

Hoogerwerf:

Yes, I wasn’t able to get you to come along on this adventure in the same way we usually do. I wonder why?

Stump:

Let’s just say there were conflicts with my schedule. But I will say that one of the main motivations behind this cool creatures series is to let a creature open the door to other kinds of questions we might have. And I was pleasantly surprised to realize how many interesting paths opened up when you started learning about ticks. So we’re going to follow you from a safe distance as you experienced some ticks, but then we’ll let that lead us to questions about parasitism in general and to public health and disease control, and eve how we should think about theology in light of ticks. And then we’ll come back and see if we become convinced of anything beyond disgust.

Part One: Ticks and Research

Hoogerwerf:

Sounds like a plan. Let’s get back to the trail where I was tagging along with a group of students and a professor doing some scientific research on ticks.

Unnamed Voices:

Who wants to drag? I’ll drag. There you be. Does it have a rope on it?

Stump:

Yeah, what exactly was going on?

Hoogerwerf:

I recently got connected with Will Miller, a professor of Biology at Calvin University, just down the road from our offices in Grand Rapids.

Miller:

I’m a conservation biologist by training, and I never thought I’d be doing this during the summers.

Hoogerwerf:

Will and three students—Jocelyn, Telo and Myles—were out at a nature center in Southwest MIchigan, one of many sites that they have been studying. It had rained the night before and much of the morning, which didn’t make for ideal conditions for finding ticks and as they were getting ready they were joking about how they would not find ticks

Miller:

This is the one crew that actually wants to find ticks.

Stump:

So they’re just out walking into the woods, looking around for ticks?

Hoogerwerf:

Well there’s a bit more of a technique involved, but overall it’s pretty simple.

Miller:

So this technique they’re doing is called drag sampling.

Hoogerwerf:

Will pulled a big rolled up piece of cloth out of the trunk and unrolled it. It was maybe about 4 feet by 3 feet, with a wooden stick on one side and a rope tied to the stick. And essentially one of the students walks down the path and drags the cloth along the side of the trail.

Miller:

It may seem simple, but this is like the gold standard for active surveillance with ticks, because other methods, like host sampling and things like that, we can’t actually calculate densities from them, since we don’t know what the sampling effort is. So by dragging along trails, we know how far we drag, and are able to use that as the denominator to calculate about the average number of ticks per unit area.

Hoogerwerf:

Every 100 meters or so they would stop and gather around, leaning over the cloth looking for any ticks it picked up.

Voices from the Field:

Oh, I got one. There we go, already.

Stump:

So you did find one?

Hoogerwerf:

Yeah right away. The first time they picked up the cloth there was one on it. We actually didn’t get anymore on the cloth after that, though Will did find one on himself later on in the day. That first one on the cloth though…was tiny. A nymph.

Miller:

So that’s the nymphal life stage. They tend to be about the size of a poppy seed. [colin reacts with am audible gasp]

Hoogerwerf:

Apparently my surprised reaction to the size isn’t uncommon.

Voices from the Field:

Same reaction every time. Same reaction. [laughter]

Miller:

So this, this life stage, is actually probably the one that’s most medically relevant because of how small they are, and they’re active during summer months. So they live in the leaf litter, and they have a behavior called questing, where they stick their legs up in the air and wait for you to come by. And so they just kind of sit there, and works out really well for this awesome little fabric, cloth that we can drag around.

Stump:

A nymph? This is one of the life stages of every tick?

Hoogerwerf:

Yeah, maybe we can do a little basic biology here. Ticks are arachnids. That puts them in the same taxonomic class as spiders and scorpions. They are found all over the world. Ticks go through a bunch of different life stages, similar to the way insects do, but ticks are not insects, and the stages are different.

Miller:

The ticks that we focused mostly on here are three life stage ticks. So they will have a larval stage, an nymphal stage and an adult stage—that’s the reproductive stage. They’ll feed once at each of those life stages, so they’ll get a blood meal, kind of fall off, hang on the landscape, and then molt and transition to the next life stage.

Hoogerwerf:

And ticks, of course, are parasites.

Stump:

Which means they rely on some other organism to live, which I guess we all do to some extent, but the difference with parasites is that they harm the other organism in the relationship?

Hoogerwerf:

Right. To various levels. And we’ll learn more about the specifics of that for ticks as we go. Ticks can have a lot of different hosts, including mammals, birds and reptiles. Some ticks specialize on a host—like, for example Amblyomma rhinocerotis, the Rhinoceros tick. Others are generalists that can have lots of different hosts.

Stump:

And then there is the most famous quality of ticks…the fact that they are disease vectors, carrying all sorts of bacterial and viral pathogens that get passed along, from host to tick, from tick to host.

Hoogerwerf:

And that brings us back to Will and his students because, while they do enjoy being out in the woods, and it turns out they do even have some interest and respect for the ticks themselves, the main reason they are out here is because studying ticks has a public health application.

Miller:

So we’re collecting them live. They will go back to the lab where we’ll, well, they’ll freeze them overnight. And then we’ve got a set of different pathogens that we’re looking for. And so we’re gonna run them through PCR testing in pools to look for the Lyme disease spirochete, another disease called Powassan virus—it can cause encephalitis and is an emergent health problem that we’re interested in. So we test them all for four different pathogens to understand what the risk is in the area.

Hoogerwerf:

So you can start to see why this kind of research is important and might even have some real life applications for anyone who goes outside. But ticks don’t just affect people. They also affect animals, and specifically livestock. And the students I was with actually had a pretty big-deal scientific find that has some implications to livestock. This was just a couple of weeks prior to when I went out with them. I’ll let them pick up the story. Here’s Jocelyn.

Nieze:

So it was kind of a funny story coming into finding it. We there was a miscommunication. And through a series of misunderstandings we ended up on the wrong trail. So we’re like, what are we doing over here? This doesn’t look right at all. So we just go along with it, do our dragging, and on our way back on the opposite side of the trail, we got a tick that looked a little weird, but that was also our first day really getting a good look at Lone Star ticks. And Lone Star nymphs in particular. So it just looked like a little bit of a bigger Lone Star. And then we’re like, “okay, it’s weird, but ticks are weird.” So we threw it in the vial.

Hoogerwerf:

So they take it back to the lab. That was a Friday. The next Wednesday was a lab day and so they’re at the microscopes identifying the ticks from the field.

Nieze:

I believe it was Telo that was looking at them.

Telo:

Yeah it was actually my first time observing the Lone Star nymphs under a microscope. So I see the first one is different. So I put it aside, move it aside, focus on another one.That also is different. So I’m like, “Okay, what’s going on here?” So I moved that one aside, and I look at another one,which is also different. So I’m like, “Okay, I don’t know what is going on here.” So I call Myles. I’m like, “Hey, Myles, take a look at this, because I don’t know what’s going on here.”

Nieze:

And I joked saying, “watch it be a Longhorn tick,” just because that’s been in the media a lot in different states. So we’re like, “but there’s no way.”

Hoogerwerf:

So there are three weird ticks that they are having trouble identifying. They end up identifying one of them as a dog tick, but they still have these two weird ones. Time to call Professor Miller in.

Radersma:

And we had them next to each other, which is what, when he looked at it, he was like, “Oh, those are rabbit ticks. Those are both rabbit ticks.”

Miller:

And they all said, “No, you should maybe look at that again.” So I took a second look and then I saw the other one, which was very clearly similar but different. At the same time, I said, Okay, this might be one of those things where I want to call in some extra help.

Hoogerwerf:

So one of the two did turn out to be a rabbit tick, another Michigan species, but that still left one odd one and so they got in touch with some collaborators at Michigan State University and sent them some pictures.

Miller:

Sure enough, she said, “yeah, you’ve got something here.”

Stump:

So what was it? A new species of tick?

Hoogerwerf:

Yeah, well not new to science, but new to Michigan. It was the Asian Long-horned tick. The same one Joeclyn had joked about.

Stump:

Kind of fun to make a discovery like that, but probably not good news right?

Hoogerwerf:

Not good news. So the biggest problem from Asian Longhorned ticks is probably not to humans but to livestock. And one of the things that makes these ticks especially invasive is that they are parthenogenic, meaning that a female can lay eggs without mating.

Stump:

That sounds like a bad recipe. You never want a dangerous pest that can replicate itself as many times as it wants without having to find a partner.

Hoogerwerf:

Right. A pretty good strategy for spreading out in a new place after maybe taking a ride on a bird or rodent. But you need more than one tick to say that a population is established, even if it is parthenogenic. The CDC has some guidelines for that.

Miller:

For it to be an established population, we need six of one life stage, or two or more life stages.

Hoogerwerf:

After confirming the one in the lab, they went back and they have found two more in the same lifestage. So it’s still considered a report not an established population. But it has definitely generated some interest.

Miller:

There were actually agency biologists that were working on an early action plan for this species. It was still in draft form, but it then this all kind of kicked on a steamroller effect of making sure that they had what they needed, because it’s an agricultural pest, they wanted that information out to producers and vets.

Stump:

It’s not every day that we get to see behind the scenes of the work of science and put together the pieces that connect the scientific work to everyday people—in this case, walking trails dragging a piece of cloth, keeping careful notes, looking in microscopes, that all leads to information that has a real effect on people walking their dogs in local parks or to farmers who rely on healthy animals for their daily income.

Miller:

Right now, the biggest part of the research that we do, and the research that many folks that are doing surveillance work are doing, is gaining information so that our cooperators—public health agencies, Department of Agriculture—have the information that they need to do the outreach that is important to their mission. So educating the public is a huge aspect of the process now, because without a preventative and without a silver bullet management strategy, what we want people to do is understand, take measures to protect yourself, protect your pets and protect your cattle.

[musical interlude]

Part Two: Lyme Disease

Stump:

Okay we’ve learned a bit about ticks and we got to see some students involved in research that starts to link to everyday people and health and economics. I’m not sure I’m convinced yet to keep one as a pet.

Hoogerwerf:

Well, no, I wouldn’t advise that. We can’t ignore the facts. Ticks really do present a danger to humans.

Stump:

That danger comes not necessarily from the tick itself but from the diseases transmitted by the ticks. Of which there are many around the world. Tick-Borne Encephalitis and Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever are significant global health threats. In the United States, ticks are responsible for transmitting Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Anaplasmosis, and many other rare but severe diseases. But the most prevalent by far is Lyme disease, which is spread by ticks, but it is actually a lifeform of its own as well. A bacteria.

Tsao:

So the bacterium that causes Lyme disease is called Borrelia burgdorferi.

Hoogerwerf:

This is Jean Tsao.

Tsao:

I am a professor at Michigan State University

Hoogerwerf:

Jean works both with the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife and with the Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences in the veterinary school. She has been involved in studying the Borrelia burgdorferi bacterium for over 20 years.

Stump:

So this is a single celled organism, so not something we’re going to be able to see except through a microscope. But just because it’s a single cell doesn’t mean it’s not still complex with specially adapted characteristics. These things have been evolving for billions of years.

Tsao:

It’s a spirochete and that’s in the group of bacteria that look like corkscrew shaped organisms and spiraling. And that spiraling is interesting to know about for its biology because it helps it really move through more viscous thick material.

Story:

It has an amazing set of flagella, which are these whip-like structures.

Hoogerwerf:

This is Craig Story. He’s an immunologist and teaches at Gordon College.

Story:

And we have a lot of ticks and lots of Lyme disease in New England. So it’s something I’ve been following as an immunologist and as someone whose family members, extended family members have had Lyme disease.

Stump:

Back to the flagella—

Story:

And unlike the maybe bacterial flagella people are familiar with, the sort of rotating, whip-like rotating appendage. This one is inside the actual bacteria and it causes it to have a corkscrew shape and it makes it able to burrow through viscous, thick, syrupy substances.

Hoogerwerf:

Being able to hang out in the skin comes in really handy because the blood is where a lot of the immune cells are that would want to fight a foreign invader.

Tsao:

—in the blood is dangerous because that is where more of the host’s antibodies will be flowing through and so in a way, the way I think about it, is that it spends some time in the blood because it can then move further around in the body of the host to get away potentially from the bite site at first where there could be antibodies getting recruited to and such. But then it also potentially will then be facing other antibodies in the bloodstream that can kill it. And so being out in the more skin type tissues, whether it’s your actual, our skin here or in you know, the endothelial cells of organs, then they’re just a little bit more protected.

Stump:

Evading antibodies is one challenge it has to deal with, but Borrelia’s survival depends on more than just hiding within the host.

Tsao:

So what is really interesting about the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, is that it needs to live in both the tick and the host, which is a vertebrate host. It cannot live outside in just nature, in the mud, or on the leaf.

Hoogerwerf:

It turns out ticks and vertebrates provide pretty different conditions for bacteria. For one thing: the temperature. In a tick, the bacteria pretty much needs to deal with whatever temperature it is in the environment—

Tsao:

So it’s going from, you know, a room temperature, which could be outdoors 70 degrees, but it could be 50 degrees or 40 degrees or zero degrees.

Stump:

But in a mammal host it’s going to be pretty constantly 90 to 100 degrees.

Hoogerwerf:

Also the chemistry is really different inside ticks and in vertebrate hosts. So in a tick, the conditions aren’t the greatest for reproducing and being really active, so the bacteria is pretty much just hanging out, essentially dormant…

Tsao:

It’s barely metabolizing and it’s living in the mid gut of the tick and its numbers are not huge.

Hoogerwerf:

But when the tick finds a vertebrate and bites and starts feeding, the conditions start to change inside the tick and it starts to reproduce.

Tsao:

As it’s reproducing, it changes the molecules that are on the outer surface of the spirochete. They change to deal with the change in the different environments, the tick environment and the host environment. So then their numbers multiply, then they break out of the mid gut of the tick, they swim through the haemocyl, which is the open part where there’s the quote unquote blood of the tick, and they enter, they invade the salivary glands of the tick. And then they get injected into the host.

{ominous music starts]

Story:

So ticks are designed to bite in a way that you don’t feel them usually.

Hoogerwerf:

This is different from a mosquito, which is all about getting in and out fast. A mosquito does also have some mild anesthetics in its saliva, but not to the same extent as in a tick which has all kinds of special chemicals in its saliva.

Tsao:

The biologists call the saliva a pharmacopeia—pharmacopeia, like a cornucopia, right?

Stump:

Nice [sarcastically]. So the point is to be unnoticed.

Hoogerwerf:

Right. That’s the tick’s strategy. And the bacteria inside the tick take a bit of time to increase numbers and start moving from the tick into the host.

Story:

As much as two or three days may be required to transmit the bacteria that cause Lyme disease, which a lot of people don’t realize. If you just got a tick on that day, you don’t really need to worry too much.

Hoogerwerf:

Interestingly, even among mammals, the immune systems of the different hosts do really different things. White tailed deer, for example, are a primary host for ticks. But the way the immune system in a deer works is that it attacks the Borrelia and is pretty effective at eliminating it. It doesn’t get sick. It doesn’t pass the disease on to another tick. It’s not a reservoir. Not like the white-footed mouse. The immune system of the mouse doesn’t eliminate the bacteria, it just doesn’t seem to care too much about it at all.

Tsao:

And so the spirochete can then just continue to live on in that host.

Stump:

And then the next tick that bites a mouse picks up the bacteria?

Hoogerwerf:

Yeah, that’s the idea. And the cycle continues. That’s what makes it a reservoir. There are some other species that act as a reservoir too.

Stump:

Ok, but in humans, there’s something else that happens.

Hoogerwerf:

Right. Humans are not a reservoir, we are not a part of continuing the lifecycle of the bacteria. Our immune system does attack borrelia. That’s actually part of the problem.

Tsao:

it’s not the same way that the white tailed deer does, and then it nips it. And it’s not the way the white footed mouse does it, which is to tolerate it. You know, ours fights it. And because of that fighting, that’s why we have disease. So the Lyme disease spirochete is an example of an organism that—it’s not secreting any toxin or anything that makes us sick. But it’s really the fact that we are, our body recognizes it as foreign and wants to get rid of it. So it mounts this immune response. And that’s why we then feel achy and not happy basically.

Hoogerwerf:

Ok, so if a tick bites a human, and manages to get away without being detected for quite a while, 24 to 36 hours usually, and the Borrelia finds its way into the human. That’s when problems start.

Story:

But once it gets in, it can cause a local inflammation, that little red rash, and you probably have heard of the bullseye rash. It’s a sign that the bacteria are literally moving their way slowly through your skin.

Stump:

This early stage might not be anything more than a rash, might not cause any pain and might not even be noticed. And the rash doesn’t even occur in all cases, though it does probably around 70 or 80% of the time. But if nothing is done at this stage the symptoms can get more severe.

Story:

That is going to lead to wider dissemination or wider spread of this nasty bug throughout the body. And it can cause all kinds of more concerning symptoms such as paralysis of nerves, hearing effects, neurological disorders.

Hoogerwerf:

The good news is that because this is a bacterial infection, treatment can be pretty simple and effective with antibiotics, especially early on.

Stump:

There’s another thing you hear about Lyme disease though, which is that symptoms last even after antibiotic treatment.

Story:

Persistent post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. They sometimes will call that PTLDS. And it’s a real thing that somewhere in the range of as many as 20% of people have sort of long-term cognitive or weakness or tiredness or just something is different, something is off, after they have been treated for Lyme disease. And it’s a little bit of a mystery in the sense that you may not be able to, you’re not able to find, you know, the actual parasite in the body anymore. The Borrelia is gone. So then what’s causing it, right?

Stump:

We might also think of some other maladies too—long COVID or migraine headaches or chronic pain. When the medical establishment doesn’t have a clear understanding of what is causing an illness patients can often feel dismissed or ignored. And that can lead to distrust in medicine as a whole and patients will often look to alternative treatments.

Hoogerwerf:

It may even be true that alternative medicine communities end up treating patients better, or at least with more empathy. There is a valid critique that the medical establishment may be so focused on evidence-based protocols that for patients who suffer from something that doesn’t have a lot of research or answers, it can feel like their suffering doesn’t matter.

Story:

So I can understand why people would be frustrated and I think physicians need to show you know a lot of empathy and compassion for something that’s really happening meanwhile keep our eyes open for ways to intervene in that in that process

Stump:

While Lyme disease still has a bit of mystery around it and can be the cause of a lot of suffering, it is also something that people can have some power over protecting themselves against. And that brings us back to the ticks.

Hoogerwerf:

There does seem to be a growing fear of ticks and the harm they can cause, either from Lyme disease or even the other more rare, but potentially more devastating diseases. And it can lead people to avoid doing the things that might put them at risk.

Tsao:

You should be aware of this issue, right, but by itself, that might be scary. And it might cause people to decide they don’t want to go out into the woods or not, not to garden. And we don’t want that necessarily because there are other researchers, scientists, medical folks who have found that being outside in nature can be very beneficial for your health, mentally, spiritually, you know, physically.

Stump:

There are a few simple things you can do to protect yourself from ticks

Story:

Oh by all means, you know, go in the woods, wear light clothing. If you’re really in a heavily tick-infested area, there are things you can actually put on your clothes.

Hoogerwerf:

For people who are out a lot in places where ticks are bad—which you can find out by checking local health departments—you can treat clothes and footwear with permethrin and using regular old bug spray will help a bit too. But even more simple is just to know where ticks might be, check for them when you may have been exposed, and know how to remove them if one does bite. There are also places you can send ticks in to get tested, but interestingly, I learned that most recommendations, including by the CDC recommend you not relying on these services, especially for treatment decisions. Testing will often reveal diseases that might have been present in a tick but weren’t actually passed on and might end up causing unneeded anxiety or fear. If you were bit and don’t know how long, you can save the tick and watch for symptoms. Of course, if any symptoms arise, you should contact a physician for advice or for treatment.

Stump:

Being outside, especially in places where ticks are known to hang out, comes with some responsibility. It doesn’t mean stay out of the woods or off the trail. That’s no different than grabbing sunscreen or checking the weather.

Tsao:

And then make it part of your habit for going outdoors, it doesn’t become as burdensome. And I think I would hope it could empower you to then feel better about being outside and enjoying outside.

[music]

Part Three: Parasitism and Theology

Stump:

Ok, so we really haven’t done anything here to put a better light on ticks. If anything we’ve done the opposite.

Hoogerwerf:

Maybe. We’ve definitely highlighted the danger they pose. But it’s interesting that it’s not actually the tick themselves that are causing problems, it’s the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria in the case of lyme, or other bacteria or viruses that are really doing much of the harm.

Stump:

Are you suggesting that we reserve our disgust more for the bacteria than the tick?

Hoogerwerf:

Well I don’t know about that either. It’s not just the tick and the bacteria.

Miller:

We’ve got all these different players. We’ve got deer who got white footed mice. We’ve got the tick itself, we’ve got the bacteria. And then on top of that, then we can consider the role that plants play in providing environment.

Hoogerwerf:

All of these things are really just trying to be creatures in the way that they have evolved to be. It happens that ticks and borrelia evolved to be parasites.

Miller:

So I’ll often play this little game in class. So I’ll put a picture of a tick or a mosquito up on the board, and if we were to walk along this trail for long enough, I could likely spot these little white flowers that will often grow at the base of trees.

Hoogerwerf:

He’s talking about Indian pipes, a flower that grows all over the United States that has lost the ability to photosynthesize, because it has turned to parasitism—it steals nutrients from mycorrhizal fungi, actually a fungi that is working in a mutualistic relationship with trees.. Anyway. There are other parasitic plants too. Indian Paintbrush and mistletoe for example.

Miller:

What’s the difference between a tick and those, well, one affects people, and then one is seen as beautiful and part of the landscape.

Hoogerwerf:

So there’s obviously some cultural interpretation in our idea of parasitism.

Stump:

Parasitism is a strategy that has been around for a long time. There is evidence of parasitism going back over 500 million years. And there are a lot of different versions of parasitism. A parasite doesn’t always kill its host. In fact, a lot of times, it’s to the advantage of the parasite to keep the host alive for as long as possible.

On the other hand, there are some gruesome-sounding examples of parasites that have pretty extreme effects and even take over the neurological systems of their hosts. Toxoplasma gondii is a parasitic protozoan that uses cats as its definitive host. But like Borrelia it has multiple hosts during its life cycle. When Toxoplasma infects rodents like mice, it alters their behavior so it can get back to cats—making them less fearful of cat odors, and in some cases, even attracted to them. That’s good for the Toxoplasma but probably doesn’t end well for the mouse.

Hoogerwerf:

That certainly seems to fit with the common view that parasitism, as a life strategy is bad. And not bad as in ineffective—bad as in evil. Especially in comparison to other kinds of life strategies like mutualism where creatures create beneficial relationships with one another, sometimes becoming so reliant on each other that they appear to be a single creature. But we might need to consider our own biases when thinking this way.

Miller:

Ticks are doing ticky things, and they’re being ticks, and it there’s all kinds of factors at play that influence the risk of disease when it comes to parasitism and questions surrounding things like natural evil, I’ll often suggest maybe we need to think about checking an anthropocentric lens when we’re thinking about some of these problems.

Stump:

This is part of the way nature works. When we have only a superficial view of these things, it’s easy to overlook or dismiss aspects of nature that don’t fit our views so easily. That lets us confirm and entrench views that aren’t actually accurate. We can end up having a cartoon-version of reality. Then, when something like this is brought up—or more famously Darwin’s problem with the parasitic wasps—it can lead us to questioning, or even throwing out the whole worldview upon which our faith rests. God must not really be good. Instead, we ought to be able to lean into these examples, and have them inform us in a more nuanced way. These difficult parts of nature could actually point us to deeper truths about how God has designed things from the beginning: it’s not an absence of pain and suffering, but somehow in a cruciform way, even these are parts of God’s good world. That should be our starting point—rather than starting with a cartoon-version of what is really good, we start with our good God who declared creation to be good. I’ll note that in the Adam and Eve story, they were prohibited from eating from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. That seems to suggest, like the book of Job does, that some things are too wondrous for us to know and that we need to rely on God to guide us into these mysteries. So we start with a good world, and now discover that it has parasites in it. Does that mean we reject our starting point? No, it means that we’re led deeper into the mysteries of how the world works… but we’re also called to subdue the chaos in the world. I don’t think that means eradicating the ticks, but maybe it does mean developing medical treatments so their natural way of being does not result in sickness and death.

Hoogerwerf:

Have you solved the problem of pain and suffering??

Stump:

I’m afraid not… I’m mostly just rambling, trying to gesture toward some things we can say about it from the perspective of people who affirm the goodness of God and the goodness of creation, and don’t pretend not to see things like parasites.

Hoogerwerf:

Our story with ticks gets even more complicated, because even with all the parasitism, there’s also cooperation. Because ticks rely completely on blood for their nutrients and feed on nothing else, they aren’t able to get many of the essential vitamins they need to survive. To solve this problem, ticks have formed a mutual relationship with different bacteria which live inside them, endosymbionts, which are able to produce the necessary vitamins and in return the bacteria are provided a stable environment to live and reproduce.

Stump:

So here’s a parasitic organism, the tick, which itself has parasites — it is host to bacteria and viruses, some of which cause harm to the ticks and to humans, others of which have found cooperative ways of surviving with the tick, to the point that neither organism can exist without help from the other. And the tick also exists in an ecosystem where they become prey to many other creatures.

Part Four: Are Ticks Cool?

Hoogerwerf:

When you start to look closely and curiously, what seem like simple assumptions—ticks are disgusting, parasitism is evil—those things start to become more complicated. What do we do with all this complexity?

Stump:

Well at least from a practical standpoint, it tells us that when we’re dealing with public health problems, we can’t ignore ecological issues. There’s a movement that’s developed from this realization called One Health.

Miller:

One health has been this movement that’s come about from a variety of different biological disciplines—medicine, veterinary medicine, conservation biology—that looks at the mutual health benefits of humans, animals and environmental health. Okay, so rather than looking at those things as siloed, things like environmental health, we could think of that as conservation biology or wildlife biology, rather than looking at a siloed discipline, the one health perspective combines these three avenues together and looks for how do we promote mutual health connections between all of these different systems. So it’s much more holistic in the way that it’s handling some of these issues.

Tsao:

We need all these people to work on these various different aspects to reduce the risk that people will then contact ticks. So you can start with the human physician and then the the public health department you know trying to educate people on the methods to prevent ticks you have veterinarians who play a large role in that as well…

Hoogerwerf:

And when you to start to see physicians working together with disease ecologists and wildlife experts, and parks and recreation departments, and landscape designers, and veterinarians, you not only find new ways to improve public health, you also find ways to solve ecological problems. And maybe even more than that—when scientists, doctors, conservationists, and community members work together, we begin to see that health isn’t something that belongs to humans alone. It’s shared. That realization starts to reshape how we think about our place in the world. Not as separate from nature, or above it, but as part of a much larger web of life—where the well-being of people, animals, and ecosystems are all deeply intertwined.

That’s a big idea. And it brings us back to the question we started with.

Stump:

Are ticks… cool?

Hoogerwerf:

Yeah. Well, I asked this question to a bunch of the people we talked to. Here’s Jean Tsao:

Tsao:

[laughs] I think they’re very cool as biological creatures. I think about how without eyes, well, some ticks have eyes, but they’re not like eyes like flies. How do they find a host? How do they deal, how do they battle with the host’s immune system? How do they find each other? And I think just the basics of biological life, you know, I think how does this little critter do it? And they have found ways to do so over millions of years. So I think that’s pretty cool.

Stump:

Craig’s answer maybe came a little closer to public sentiment, at least to start.

Story:

Nah, I hate ticks.

Hoogerwerf:

Yeah, but whether or not he’s mostly joking here or mostly not, he had more to say:

Story:

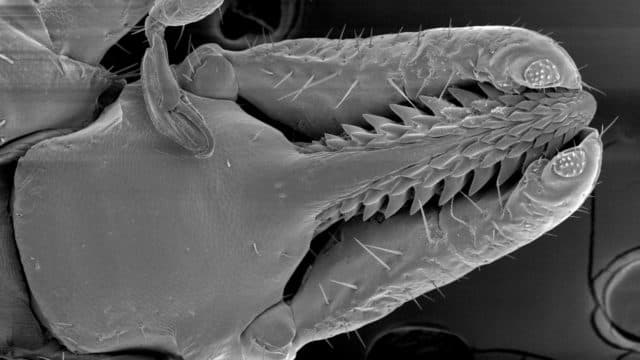

In a sense, of course, I believe all of God’s creatures are cool in a way and amazing. And if you’ve ever seen one up close, that is on an electron microscope image, it’s really remarkable to see the adaptations they have for survival. So as a Christian, I wonder sometimes, why God did you make ticks? Why did you make mosquitoes? And this part of God’s creation and this is part of the abundance of the creation which includes every kind of type of animal that you can imagine. Including ones that cause illness.

So not only is the tick in a way cool in the sense that it’s amazing—it’s a machine for reproducing itself. It hangs out at the edge of leaves waving its arms waiting for a deer to walk by or you and just latches on and you know has all these adaptations to obtain food and you know again reproduce itself. So it does what it does very well. And you know what we have to do is just be able to live with that, be able to see its own reason to be as it is.

And so what is its reason to be? It’s part of the ecosystem. It’s part of what keeps the stronger animals like deer surviving. It’s, I think, the world of God’s creation is way more complicated than most people can appreciate, just from what most people know about how these kind of food webs work and parasites and so on.

Radersma:

I think ticks are cool.

Hoogerwerf:

That’s Myles again. And for him and for Joecyln and Telo, it has a lot to do with going in a bit closer to start seeing the details that aren’t always obvious to the naked eye.

Radersma:

But when you actually look at it under a microscope, there’s so many little details, which, coming from a faith background, to me, it’s like, wow. This thing that most people never even think about or never even see has all these tiny little, just those tiny, little spikes. Like, I don’t know what they do. I don’t know why they’re there. But for some reason, God created them on this tick. Yeah, I find it cool.

Nieze:

There’s just, like, so much depth to such a little, like an arachnid, something so small and so like, what we maybe as humans, would ignorantly call insignificant. And yet there’s so much detail in that alone, and I think that’s been really cool to watch and see and learn more about.

Telo:

I believe that everything is created beautifully by God, and so when you kind of go out there, look at the ticks, look at them under a microscope, you learn how to appreciate the beauty side of it, because ticks are not inherently bad creatures. It’s just the bacteria that they carry that causes the disease. But like you learn to appreciate things in their more natural form.

Hoogerwerf:

And even if you can’t get on board with the beauty of a tick under a microscope, maybe there’s a different appreciation to have at least for studying ticks that can be connected to the work of science to promote healthy people and environments.

Radersma:

I’m studying these diseases that are right here, right now, and seeing the impact it had, even just last summer on like, public health messaging about, “oh, these is where ticks are really bad, and this is where ticks are really, they’re not bad.” And seeing those impacts kind of affirm to me, not just in what I want to do, but also in, like this is where I meant to make a difference in the world, like I just mentioned. So I think there is a big faith aspect in my personal journey, in that, just in my vocation, because that’s a big part of my faith and my life.

Stump:

The work of science for a lot of people comes from a deep curiosity, to want to know and connect with the strange and marvelous mystery of being alive in this place. For scientists, that can be a lifelong journey and it can also bring up hard questions. There is a lot of beauty in the world and conserving beauty is a worthy goal but we also need to step back and ask questions about what we’ve traditionally seen as beautiful and whether we might be able to expand that notion.

Miller:

What does it mean to be a steward of something? And I think that these challenges of one health perspective, has kind of helped me to embolden that perspective, because if you think about conservation history, if you think about even how we talk about stewardship in Christian circles, there’s often this idea that, you know, nature is over here and humans are over here, and we want to be benevolent caretakers of this, but ultimately, we can extract things from nature and use it in certain ways and not be affected by the consequences. Then I think things like the pandemic, things like the Lyme disease system that we study right now, show that there are very real and important implications for how we relate to nature. What is the human nature or human creation relationship supposed to entail?

Stump:

In the Christian creation story, Adam—made from the earth itself—is given the chance to name the living things. We often think about this naming as an immediate blurting of words. “Giraffe!” “Weasel!” “borrelia burgdorferi!” But maybe the story was implying that the act of naming was really more like an act of coming-to-know, a slow and careful approach that would involve some study and observation.

Miller:

And in that story, I see a lot of this—I like to think of the eager anticipation of God waiting to see what we’re going to learn about the creation, and by extension, then learn about God through those interactions. Sometimes, I think we’re scared of that in Christian circles. There’s something that feels uneasy about, you know, having this wonder and all about the creation around us, and having that draw our attention.

Hoogerwerf:

Will brought up Romans 1:20 here.

Stump:

“Ever since the creation of the world God’s eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been seen and understood through the things God has made. So they are without excuse.”

Miller:

And so then I think about the effects of humans in the landscape, and how ecological balance can be distorted. So that, you know, we were talking about ticks being ticks, and doing what they were created to do, how that may run rampant, if ecological balance is off due to the effects of people. And so it all kind of comes back then to this holistic, you know, One Health approach to creation care. The health of the land is the health of the people. And I think that that is a biblical narrative and a biblical land ethic that we can really grab a hold of.

Hoogerwerf:

So are ticks cool? Maybe that’s not even the right question exactly. This world, that is filled with life and with intricate relationships and tiny complicated things, is undoubtedly cool. That it exists, that we get to see it, sometimes as close as 1000x magnification, that is very cool.

That disease and sickness are part of all this? That’s harder. In some ways, we can say that things have gotten off balance and that is partly our fault. But I don’t think we are to blame for all the hard things either. Parasitism seems to be a way of life and it means that something is going to suffer. For any living thing to be a part of this world, means that something else must not.

Stump:

In the beginning you asked about whether ticks might be seen as worthy of study or whether they could be seen as beautiful. Well, to some degree, beauty is the eye of the beholder…and I’m not quite there yet with ticks, though I can appreciate hearing from the scientists who have found some beauty in this, of all creatures. I’m definitely convinced that they are worthy of study, and maybe not only because of the way studying them contributes to human health, but maybe even just for their own sake, because when we do so, it leads us to these interesting questions you’re asking. And I definitely believe that they are part of this enormous, interconnected system of life that God created and called very good.

Credits

Hoogerwerf:

That’s our show. Thanks for listening.

And thanks to Jean and Craig and Will…and his students, Jocelyn, Telo and Myles, for their curiosity and scientific work which brings all of us joy of knowledge but also real-world human and ecological health benefits.

Language of God is produced by BioLogos. BioLogos is supported by individual donors and listeners like you. If you’d like to help keep this conversation going on the podcast and elsewhere you can find ways to contribute at biologos.org. You’ll find lots of other great resources on science and faith there as well.

Language of God is produced and mixed by Colin Hoogerwerf. That’s me. Our theme song is by Breakmaster Cylinder. BioLogos offices are located in Grand Rapids, Michigan in the Grand River watershed. Thanks for listening.

Additional Resources

Ticks Up Close

Images of ticks from an electron scanning microscope, courtesy Seth Gerard, a former student of Craig Story.

A scanning electron microscope image of a deer tick at 25× magnification (5.0 kV), revealing its intricate anatomy in striking detail.

A scanning electron microscope image of a deer tick’s mouthparts at 110× magnification (5.0 kV), highlighting its sharp, serrated feeding structures in extraordinary detail.

A scanning electron microscope image of a deer tick spiracle at 330× magnification (5.0 kV), revealing the intricate structure of its respiratory opening.

Featured guests

William Miller

Jean Tsao

Dr. Jean Tsao has been studying the Borrelia burgdorferi bacterium for more than 20 years. She has appointments with both the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife as well as the Department of Large Animal Clinical Science as Michigan State University.

Craig M. Story

Myles Radersma

Calvin University Student

Jocelyn Nieze

Calvin University Student

Telo Onyango

Calvin University Student