COP30 is Coming. Here's What I Learned At Last Year's Summit

Ahead of COP30, I reflect on stories from last year's UN Climate Change Conference that reshaped my view of community and responsibility.

Colin at COP29. Photo by Jim Stump

Thousands of delegates and observers will convene in Brazil for COP30 in just over three months. Ahead of this meeting, Colin Hoogerwerf reflects on his experience attending last year’s summit in Baku, Azerbaijan.

Colin arrived at COP29 hoping the experience would relieve him of the fear that he wasn’t personally doing enough to combat climate change. Instead, hearing stories from individuals personally impacted by the changing climate redoubled his commitment to living sustainably.

First Impressions: Entering COP29

When I first walked into the huge plenary room in Baku Azerbaijan, last November, with the UN flag standing on the stage and the rows and rows of desks with little country plaques and microphones, I felt a sense of relief.

This was a place where things happened, it seemed. There was formality here and gravity and action. There was a plan.

I’ve been worrying about climate change and the environmental crisis for a long time. I’ve done the easy things—changed my light bulbs, put the recycling out each week—and some harder things—I’ve turned my yard into a garden and I’ve tried (though rarely succeeding) to reckon with the monster of consumerism that has its grip on me. I’ve wondered whether it’s enough.

But here was the whole world, sending its professionals to hash it out in meeting rooms, to solve this problem in ways that none of us can on our own. Maybe I could let go of some of my fear that I wasn’t doing enough?

Those were my feelings as I entered the main room at the UN’s Conference of Parties and took it all in.

I sat down and waited for the session to start. After a while a few people nearby started leaving and someone behind me told me that the session had been rescheduled. It would start in a few hours, or might get rescheduled again.

Okay, so global meetings of 198 countries don’t always run on time.

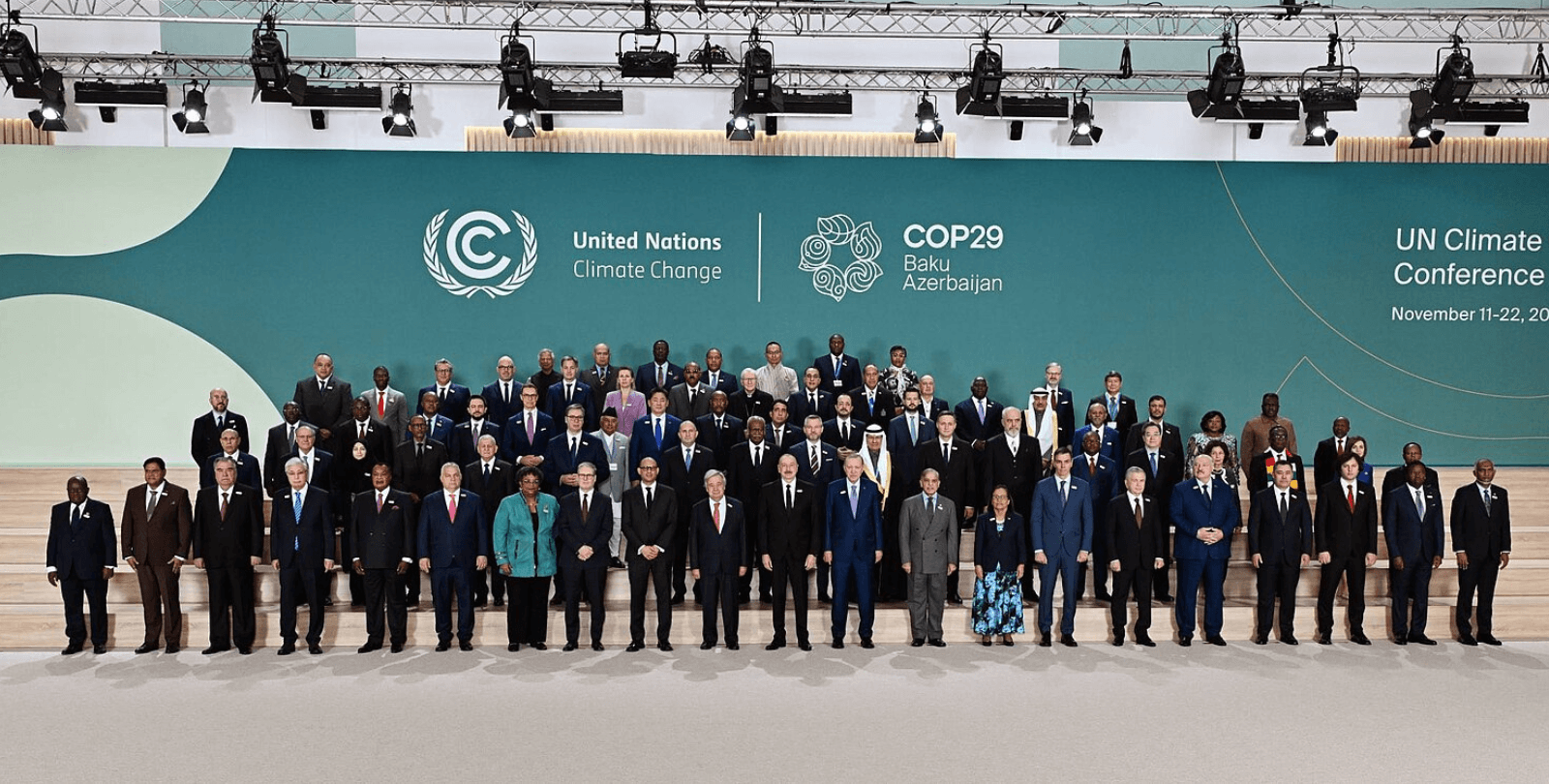

President.az, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Inside the COP Process

The main work at a COP is done by official delegates of the parties. These delegates – who are usually diplomats, lawyers, negotiators, and governmental employees – work on drafting and editing the documents that will become the official outcome of a COP, to which all parties must agree.

But the UN also grants access for Observers, who are welcome to sit in on many of the official negotiations (though not all of them). Alongside the negotiations there are constant presentations, panels, and networking opportunities.

American knowledge about COPs or the United Nations in general isn’t very high, so it’s probably no surprise that American churches aren’t exactly a hotbed for teaching congregants about the U.N. process.

But while discussion of global climate change policy is lacking from American churches and sermons, Christianity is not completely absent at a COP. This is partly in thanks to the Christian Climate Observers Program, aptly shortened to CCOP.

CCOP is an organization that brings emerging Christian leaders to the COP conferences. The team lodges together, beginning each day with devotions and learning before heading off to the Blue Zone—which is the name for the official location where all the COP meetings happen, behind the layers of UN Security. It is through CCOP that I was able to get my official observers badge and find my way to the plenary room.

There is a tedium to the kind of work that happens at a COP—long arguments over the very specific wording of a paragraph that can seem to an observer to have little importance to the bigger goals. Or an hour-long meeting of delegates complaining that they haven’t had enough time to read the document they are supposed to be giving feedback on.

UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD), CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

I can understand a bit of tedium. Work like this can’t be done quickly. While the climate crisis does call for immediacy, the work of agreeing to something as a global community is slow. Anything done quickly at this level would be sure to advantage some over others, and most likely it would be the wealthiest of countries that would gain the most advantage.

But at COP29, held last fall in Baku, Azerbaijan, there were problems that rose above the normal monotony. The negotiators had to wrestle with a complex political landscape (the United States has since withdrawn from the Paris Agreement and the COP process completely) and countries clearly had different ideas about what was important.

They did come to an official agreement in Baku, setting a goal of $300 billion per year of funding for climate help, but it was much less than most countries were calling for and it came as a great disappointment to those who came hoping to bring back news of ambitious goals.

Hope, Not in the Headlines, but in the Hallways

My time at COP29 didn’t deliver the sweeping, immediate solutions for which I might have initially hoped. The intricate dance of diplomacy and the slow grind of negotiation can be disheartening, especially to those new to the process. As the climate community now pivots its attention toward COP30 in Brazil, the hurdles for negotiations have not gotten any easier and there will be many conversations left unresolved in Baku that will need to be picked back up.

But for me, the lasting impression of COP29 wasn’t found in the official outcomes. It was in the profound encounters with individuals whose lives are on the frontlines of climate change.

Their stories transcended the policy debates, offering powerful, personal perspectives on the global crisis and inspiring a deeper commitment to action. It is these encounters, more than any official declaration, that shaped my takeaway from COP29 and reinforced my belief in the power of shared narratives.

I think it will be good to remember these experiences as we watch the world come together again, with as much dysfunction as a year ago or more, to try to solve one of our greatest challenges.

Let me share two such stories.

Breaking Barriers: Rose Omariba’s Journey to Baku

Rose Omariba is the Kenyan Chapter leader for the Laudato Si movement. She was a fellow Christian Climate Observers Program participant with me at COP29.

Rose had never been on a plane before she was offered the chance to come to Baku for COP29. Many in her community were skeptical at her choice to spend a significant portion of her savings on a flight to a country they couldn’t place on a map. But Rose felt a clear call.

She comes from the Maasai people of Kenya. The Maasai are pastoralists, relying on cows, sheep and goats for their livelihood. But these people who have learned to predict the weather through generations of handed-down knowledge can no longer do so because of the unpredictability wrought by climate change.

NoahNairobi, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Along with weather volatility comes extremes. Kenya experiences extreme flooding – a particularly catastrophic flood in spring 2024 displaced hundreds of thousands of people and closed schools for weeks – and at other times there are extended droughts. Rose told us about a Maasai friend whose 500 cows all died due to drought.

In Kenya, Rose is working to make her community a better place. She is part of an NGO developing local waste management solutions, and as an activist she is striving to energize others and create momentum.

But in this work she has also found that access to government offices and leaders, who may be located in the same towns and cities, is often kept behind barriers of appointment books and security clearances.

Upon coming to Baku, she found those same officials were walking through the same hallways and standing in the same lines for coffee and she was able to develop relationships with many of them. She told me, “Now we have exchanged personal contacts. It’s not even the official or the office contacts, but the personal contacts. And some of them were like, when can you come so that we can start thinking about how we develop your idea on waste management and social enterprise.”

The official outcome of COP29 probably won’t go a long way in helping the Maasai pastoralists or schoolchildren who must wait for the water to recede from their buildings each rainy season. But Rose returned to Kenya with important contacts and with a faithful resilience that will drive her to do the good and important work she has started.

Rising Seas and Relocation: “It’s literally removing our soul out of us”

Litara Ieremia-Allan may be known by some as Miss Samoa 2024 or Miss Pacific Islands 2025, but it was her role as a part of the Samoan delegation to Baku that led us into conversation.

The South Pacific Islands are, in many ways, on the frontlines of climate change. Many island communities have already been forced to move due to rising sea levels, and the list of villages that will need to relocate continues to grow in many of the lowest lying islands.

Claire Charters, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

But sea level rise is not the only threat. Like much of the rest of the world, they also experience weather’s increased severity and unpredictability. Litara told us about communities who have been hit by cyclone after cyclone until they were unable to recover.

Litara helped to give us context to what it means for a Pacific Islander to be relocated. Relocation is much more than a geographical shift.

Litari said, “When you talk about displaced people in the Pacific, you’re talking about losing our language, losing our connection to places that we count as family members, and also losing our connection with our elders because we bury them in sacred places. We intentionally keep them close to us…so when big parties talk about, oh yeah, we can just move, and we hear this whole idea of climate change refugees, right for us, it’s not just being removed, it’s literally removing our soul out of us.”

The connection between land and soul is not unique to South Pacific Islanders. For many people around the world, the place where they live has deep history, attached stories, and becomes a link to their spirituality. When they are forced to leave their home, they lose the link to their history and even to their spirituality.

Knowing Stories, Taking Action: Connecting Our Decisions to Our Global Neighbors

The financial decisions made by global bodies like the UN or at a COP can feel abstract, especially to some Americans who are more insulated from climate effects. That’s why it is helpful to hear from those with immediate needs that funding could address.

The conversation around funding for the effects of climate change usually revolves around two areas: mitigation and adaptation. For a long time mitigation was the main interest—what could we do to make sure we avoid the bad effects of climate change so that we don’t have to adapt? Talking about adaptation felt like admitting defeat.

Now, adaptation—including things like relocating a village, learning new agricultural techniques, or building seawalls—is an unavoidable reality (and often an expensive one). But adaptation can still bring about quality lives and livelihoods.

The comfort I felt when arriving in Baku – that someone else would take care of this problem – was a false comfort. There is no ‘someone else’.

If comfort and ease are on the near side of mitigation and adaptation, then suffering is on the far side. If we put off mitigation and deny the need to adapt to new conditions, suffering will be greater. That suffering will take place first in low lying islands, polar and tropical areas, and the least wealthy nations.

There can be some pain associated with both mitigation and adaptation. After all, any kind of problem solving causes a bit of pain. The work of reducing fossil fuel emissions and adapting to a new climate reality will require some sacrifice.

While sacrifice and suffering surely have some overlap, Christians, at least, might have a helpful way of thinking about this. Sacrifice includes pain. Jesus’ sacrifice went as far as death. But there was a point to it. Sacrifice works toward a vision of something better.

The world does not seem poised to find the funding to do the work that needs to be done to help those most affected by climate change. The countries least affected are also the ones contributing the most to the problem. While many countries are setting new goals, the need for funding grows faster than the funds.

How will we respond to the suffering that is inevitable when we cannot respond to the needs of those calling for help now?

Keep exploring with BioLogos.

Enjoying the article? Sign up for content that explores the intersection of science, faith, and wonder, delivered right to your inbox.

I think the answer to that question will depend on stories and relationships, both of which help me to connect my own decisions and actions to the possibility of the suffering or contentment of my neighbors around the world.

Sacrifice, like any spiritual virtue, takes practice. Eventually we learn that what we give up, if done thoughtfully and respectfully, might actually be a gain, often for us and our neighbors near and far.

The Work Ahead is Ours

A lot of people ask ‘what can we do?” It’s not a wrong question – it’s just that there’s not one right answer. If we went through the world with eyes toward the growth that could happen through sacrifice, a lot of answers might start to arise, different for each person, and our imaginations might open to new possibilities.

The comfort I felt when arriving in Baku – that someone else would take care of this problem – was a false comfort. There is no ‘someone else’.

A COP is only every individual who shows up or follows along. COP30 will pick up where they left off in Baku, and surely the work done there will be better than no work at all. But the future of the world cannot be laid upon the success or failure of the COP negotiations.

A lot of people ask ‘what can we do?” It’s not a wrong question – it’s just that there’s not one right answer.

When we share stories, we connect ourselves to each other, and when we are connected we will do what needs to be done—yes, through local, federal, and global policy—but also by re-visioning our world as a connected place where every decision we make is one that has ripple effects.

Rose and Litara each had a chance to address Christians in the Western Hemisphere. I’ll let them end with their words of wisdom, advice, and supplication.

“Let’s not continue preaching the gospel of heaven, but preach the gospel of people getting converted here where we are, so that when we preach to people about the heaven that we do not know, we’ve already made our Heaven down here.” – Rose

“There is something in you that goes off in your gut when you are moved by something. And I just want to encourage anybody who’s listening that God has given you a sense of justice. And so could I maybe ask, why is this not personal to you? Why is it not a sense of wanting to do right by another? If you proclaim that you follow a higher power, could it be that you’re not connected? Could it be that you’re not educated enough in it? My challenge would be to make it personal to you. If you feel removed, read about it, watch a video, visit the place, see it firsthand, and I guarantee you, your gut will tell you that there’s something wrong. So sometimes a lack of compassion comes from a lack of exposure. So expose yourself to what we’re facing.” – Litara

About the author