What the Scopes Trial Meant: Bryan, the Protestant Modernists, and Science

How did Protestant modernists encounter science? Historian Edward B. Davis explores their response through the lens of the Scopes trial.

Brown Brothers, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

How did Protestant modernists encounter science? Historian Edward B. Davis explores their response through the lens of the Scopes trial.

On its one hundredth anniversary, historian Edward B. Davis draws on rare archival sources to explore how Protestant modernists encountered science at the time of the Scopes trial. His research offers new context for understanding Bryan and his religious opponents and traces a path from the trial to today’s intersection of science and faith.

Revisiting the Scopes Trial, One Century Later

This July marks the one hundredth anniversary of the most famous event in the history of American religion and science, the trial of John Scopes for teaching evolution in a rural Tennessee high school. The rookie teacher was convicted of violating a new state law prohibiting public schools “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man had descended from a lower order of animal.”

Ironically, both the prosecution and the defense wanted a conviction. Responding to a solicitation from the American Civil Liberties Union, the Dayton school board had asked Scopes to stand trial, hoping to find him guilty so the law itself could be overturned in higher courts—a strategy that ultimately failed.

Scholars have generated an enormous literature related to Scopes in the century since it happened. WorldCat database returns more than 1,200 books catalogued with “scopes trial” as a keyword, including more than 500 with that phrase in the title of the book or one of its chapters.

Why did I write one more book about a topic so well explored? Serendipity.

In this leaflet, Schmucker used sexual selection to connect an eternally existing nature with a wholly immanent God who had not created its laws. Photograph by Edward B. Davis, from the author’s collection.

Discovering the “Science and Religion” Pamphlets

Decades ago, while doing research on antievolutionist Harry Rimmer before the internet revolutionized historical research, I stumbled upon a virtually unknown tract about “Science and Religion” from 1926.

The author, naturalist Samuel Christian Schmucker of West Chester (PA) State Teachers College, was prominent in Nature Study, an early form of environmental education that stressed taking students outside, Under the Open Sky, to borrow the title of one of his books. He was also a nationally known popularizer of evolution in the 1910s and 1920s, especially at Chautauqua where his lectures (illustrated with lantern slides) drew the largest crowds. Two of his books were used as texts by the Chautauqua Literary & Scientific Circle, rather like a college without walls.

He had been such a popular teacher that the science building at West Chester, dedicated twenty years after his death, was named for him—only to have his name removed three years ago when his strong support for eugenics became widely known on campus; one of my articles was cited in the process.

The Voices of Protestant Modernism Between the World Wars

When I first saw Schmucker’s pamphlet, I could not identify the American Institute of Sacred Literature, the now-defunct entity named at the top of the front cover (above). Soon I learned it was a correspondence arm of the University of Chicago Divinity School, and that Regenstein Library holds a large archive of papers and correspondence related to it.

There and in the correspondence of Shailer Mathews, the theologian and Dean of the Divinity School who supervised the AISL, I found letters from dozens of leading scientists about their religious beliefs, which are mostly unknown to historians. They were surrounded by other documents about the “Science and Religion” pamphlets, some of which were listed when I turned the page.

Ten were published between 1922 and 1931. The full set of authors and titles (see the table of contents from my book) included some important names in American history: Nobel Laureate physicists Robert Millikan (president of Caltech) and Arthur Compton (who chose Fermi and Oppenheimer for the Manhattan Project), Mathews, and the most famous liberal preacher of his generation, Harry Emerson Fosdick. All but one—Columbia physicist Michael Pupin, a Serbian Orthodox believer who was president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1925—were religious modernists.

In other words, the pamphlets were written by the very people whose ideas William Jennings Bryan most despised, those liberal Protestants who wanted to “modernize” Christianity by discarding biblical miracles and the orthodox creeds, in favor of the Social Gospel and vaguer notions of God that (in their view) did not conflict with modern science.

Intended to diminish opposition to evolution and to persuade Christians to adopt more positive attitudes toward modern science, the pamphlets were widely distributed to high school principals, university campuses, scientists, clergy, and legislators. Very scarce today, the pamphlets and their history constitute a revealing window on the Protestant modernist encounter with science, adding new context for understanding Bryan and his religious opponents at the trial.

Hundreds of books scrutinize Bryan and his fundamentalist friends, but the modernists are typically seen only as Bryan’s foil or the obvious alternative to Bryan’s folly. That is why I wrote the first book about modernist views of science and religion between the world wars: it’s high time someone deconstructed them.

A Shared Concern: Bryan and the Modernists on Social Darwinism and Morality

What did I learn? First, Bryan’s concerns about evolution and education were at least partly shared by the modernists, especially Bryan’s view that survival of the fittest undermines human decency and morality.

Bryan referred to this aspect of evolution as “the law of hate—the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak.” He detested social Darwinism, one form of which especially motivated him to launch his anti-evolution crusade: alleged links between evolution and German militarism.

Stanford entomologist Vernon Kellogg, a pacifist who joined efforts headed by his former student Herbert Hoover bringing relief to civilians in Belgium and France before America entered the Great War, wrote a book called Headquarters Nights: A Record of Conversations and Experiences at the Headquarters of the German Army in France and Belgium (1917). Kellogg portrayed the German officers he encountered as bloodthirsty Darwinians: “the creed of survival of the fittest based on violent and fatal competitive struggle is the Gospel of the German intellectuals.”

Others were equally worried, including pamphlet author Kirtley Mather, a Baptist geologist at Harvard who emphatically rejected fundamentalism while embracing socialism and the Social Gospel.

“Underneath the ancient warfare between theology and science,” Mather told readers of Atlantic Monthly in 1918, “there is an unvoiced, but very real, fear that in the last analysis the doctrine of the survival of the fittest in the struggle for existence is diametrically opposed to the conception of the brotherhood of man; that evolution according to Darwin and [Hugo] Devries and [August] Weissmann [sic] is the antithesis of Christianity according to Christ and John and Paul.”

Dartmouth zoologist William Patten, a modernist who debated Bryan on campus, taught the first required college course on evolution in the United States partly to address the same misunderstanding.

Keep exploring with BioLogos.

Enjoying our resources? Sign up for content that explores the intersection of science, faith, and wonder, delivered right to your inbox.

‘Origins prove nothing in the realm of values’: Modernists and Philosophical Reductionism

Many modernists also shared Bryan’s view that college professors were undermining the religious beliefs of their students. However, they did not put the blame on evolution. The danger for them lay in philosophical reductionism, the view that science somehow “explains away” our humanity, since chemicals have no values and we are nothing more than pre-programmed biochemical machines.

As Mathews put it once with typical wit, “Man has always felt himself to be something more than a peripatetic chemical laboratory driven by the sex instinct.” Mather, who had taken a Bible class taught by Mathews, agreed that “the administrative directive toward orderly organization of increasingly complex systems transcends the urge for survival.”

Addressing this in his pamphlet, Fosdick said, “One writes this with warm sympathy for the cause which gives Mr. Bryan such anxious concern. He is fearful that the youth of the new generation, taught the doctrine of a materialistic science, may lose that religious faith in God and in the realities of the spiritual life on which alone an abiding civilization can be founded. His fear is well grounded, as everyone closely associated with the students of our colleges and universities knows,” but Fosdick offered a different solution.

With characteristic eloquence he summarized his opinion in the 1920s equivalent of a tweet, an art at which he had few if any peers: “Origins prove nothing in the realm of values.”

Millikan’s brother-in-law, Congregationalist pastor and theologian Robert Brown, was so worried about the irreligious tendencies of higher education that he persuaded Millikan to publish a statement originally drafted by Brown about the compatibility of science and religion in the New York Times.

However, Millikan declined a further request to call on universities to hire faculty “not only [for] scholarship and character, but also [for] sympathy with the moral and spiritual ideals of religion.” In Millikan’s opinion, that would be tantamount to a denial of academic freedom.

Protestant Modernists’ Belief in Evolution and Design

A surprising fact uncovered in my research is that the modernists believed in both evolution and design, despite rejecting the traditional Christian theology embraced by many advocates of “intelligent design” today.

Indeed, Compton used that exact term when addressing an audience at a Unitarian church in 1940: “The chance of a world such as ours occurring without intelligent design becomes more and more remote as we learn of its wonders.”

Mathews’ pamphlet spoke of “a cosmic intelligence” that underlies the “rational and purposeful activity which in the course of evolution results in personal life,” while Millikan believed in a “Great Architect” who “had put the great sources of atomic power deep within the structure of the stars.”

Another pamphlet author, Princeton biologist Edwin Grant Conklin, was influenced by Harvard chemist Lawrence Henderson, an early proponent of the anthropic principle, to say almost the same thing in his controversial book, The Direction of Human Evolution (1921). A lapsed Methodist who had become a pantheist by his own admission, Conklin nevertheless believed in purposeful divine action within evolution, which “must have been guided by something other than chance. If progressive evolution is increasing the complexity of organization and increasing adaptation to the environment, it is surely no accident that organization and environment have been so correlated.” Overall, “it is impossible to escape the conclusion that evolution has revealed a larger teleology than was ever dreamed of before—a teleology which takes in not only the living but also the lifeless world.”

In a letter to classicist Theodore A. Miller, author of The Mind Behind the Universe (1928), Conklin let the metaphysical rubber meet the moral road: “The modern attitude that there is no God and no purpose in the Universe has led to a philosophy of pleasure and ultimately of despair and sometimes suicide. I believe that the best antidote for such a philosophy is the conviction that there is mind and purpose behind the universe and every individual life.”

“Scientific” Racism: Protestant Modernists and Eugenics

Conklin’s enthusiastic involvement with the American Institute of Sacred Literature is the canary in this coal mine. It came about partly because of his activities on behalf of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the largest umbrella organization for scientists and publishers of the journal Science, the premier American journal in its field.

Just as Bryan’s crusade got rolling early in 1922, the AAAS appointed a three-person committee to defend evolution: Conklin, a scientific racist who felt that eugenics was a moral imperative; Charles Davenport, director of the Eugenics Record Office at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island; and Columbia paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. With Davenport, the notorious white supremacist Madison Grant, and others, Osborn founded what was soon to be called the American Eugenics Society, which Conklin directed for most of the decade.

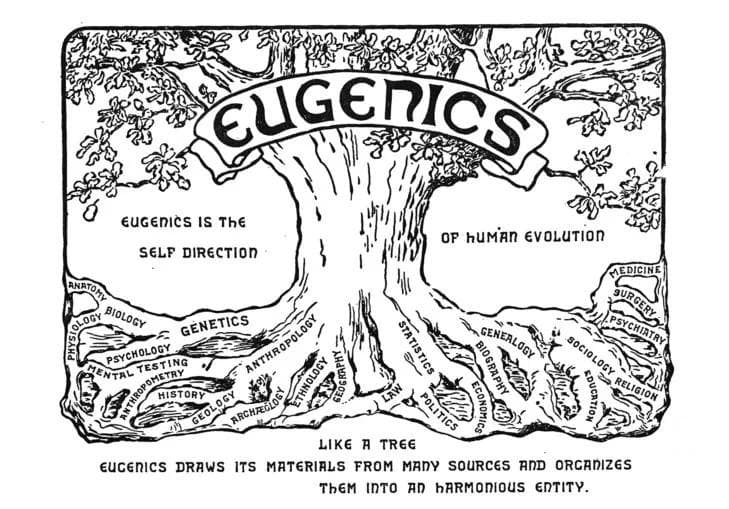

Image from Harry H. Laughlin, The Second International Exhibition of Eugenics Held September 22 to October 22, 1921, in Connection with the Second International Congress of Eugenics in the American Museum of Natural History, New York (Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins Company, 1923), 15. Three exhibits were devoted to “Comparison of White and Negro Fetuses,” “Difference between White and Negro Fetuses,” and “Racial Differences in Mental Fatigue.”

The composition of the committee speaks volumes about what the scientific establishment in the 1920s thought evolution meant: it was about not only how all species had evolved in the past, but also how humans could take charge of their own evolution in the future, as shown in the famous eugenics tree (above).

Evolution and eugenics were commonly linked with the justification of white supremacy, as in the famous exhibit Osborn designed for his museum, the Hall of the Age of Man, showing “human evolution as a process of racial hierarchical positioning and competition.”

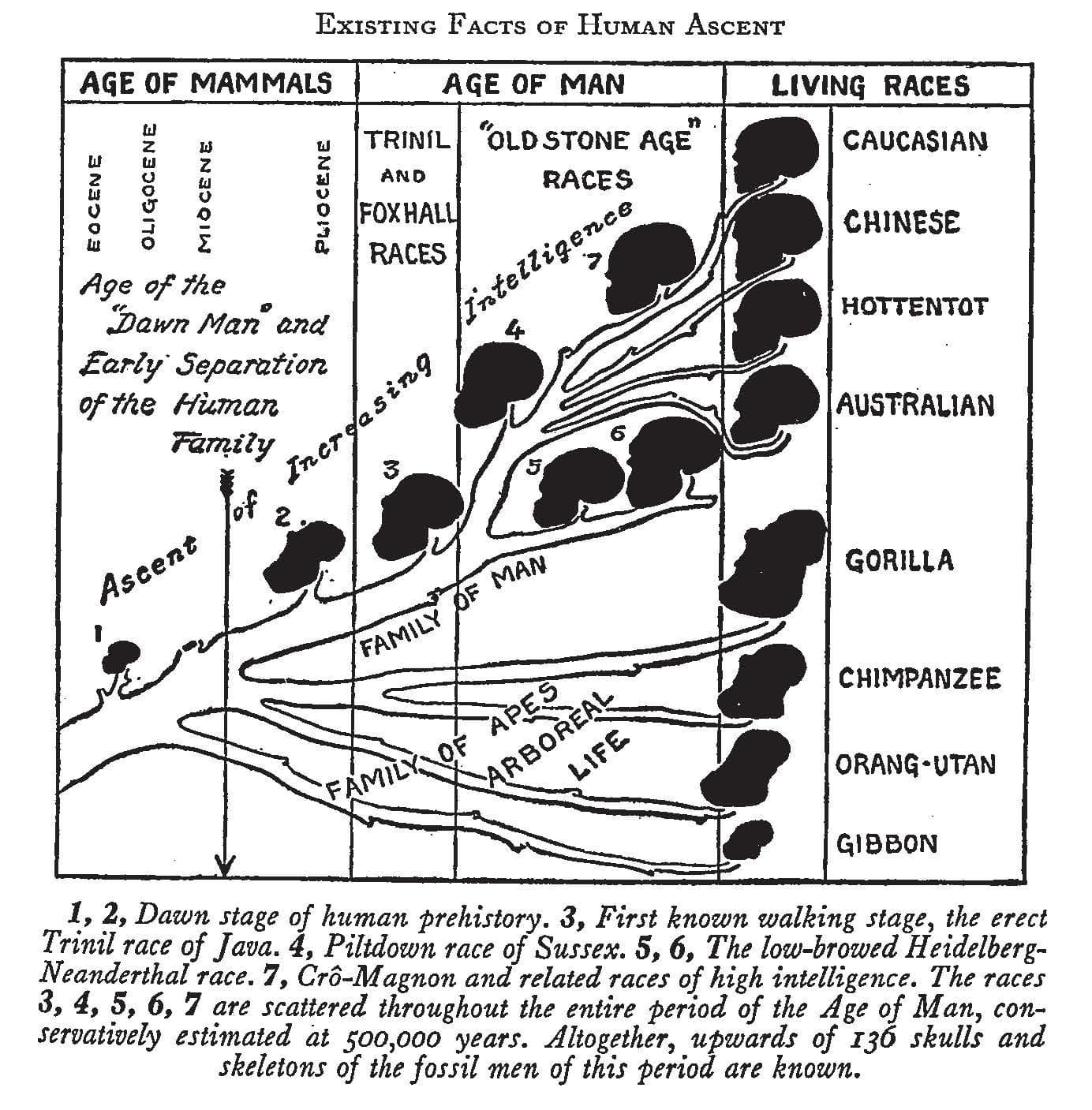

The year after the Scopes trial, fundamentalist minister John Roach Straton of Calvary Baptist Church in New York attacked the exhibit for depicting evolution as a fact, calling his essay in The Forum, “Fancies of the Evolutionists.” Osborn’s reply, “Facts of the Evolutionists,” ended with a chart (below) showing “Existing Facts of Human Ascent,” which placed the “Caucasian” at the apex of the “Ascent of Increasing Intelligence.”

“Existing Facts of Human Ascent,” from Henry Fairfield Osborn, “Facts of the Evolutionists,” The Forum 75.6 (June 1926), 851.

Bryan and Straton were no less racist than many other whites of their day, but they did not proffer a “scientific” basis for racism and they rejected the “scientific” theory of moral improvement through eugenics that was dear to many elite scientists—and to which liberal clergy flocked in droves. When Mathews assembled an anthology called Contributions of Science to Religion in 1924, Davenport contributed a chapter on “Eugenics,” while Mathews opined that St. Augustine would have appreciated “our modern knowledge of evolution and eugenics.”

One of the modernists who went to Dayton to testify for the defense at the trial, zoologist William Marion Goldsmith of Southwestern College (Kansas), a Methodist school, mingled theistic evolution, eugenics, and racism in his biology textbook, The Laws of Life: Principles of Evolution, Heredity and Eugenics (1922).

Concerning a “mixed family of white and black children,” he added that “the mother of this brood was said to have been a most vile prostitute and to have never been married.” The children “had inherited the lowest strains of physical, mental, and moral constitutions.” Unfortunately, if “the germ plasm of these illegitimates” were mingled with the “pure line” of a “respectable family,” then “many wrecked homes” might result from “the matings of such unequal young people, altho[ugh] they might be placed in an identical environment.” Goldsmith despaired of solving such problems without a better understanding of “the principles of heredity, eugenics, and euthenics.”

Of course, the textbook used in most white Tennessee schools, George William Hunter’s A Civic Biology: Presented in Problems (1914), also taught scientific racism and eugenics. It distinguished “five races or varieties of man,” with “the highest type of all, the Caucasians, represented by the civilized white inhabitants of Europe and America.”

Bryan’s Visualization of the “Descent of the Modernists”

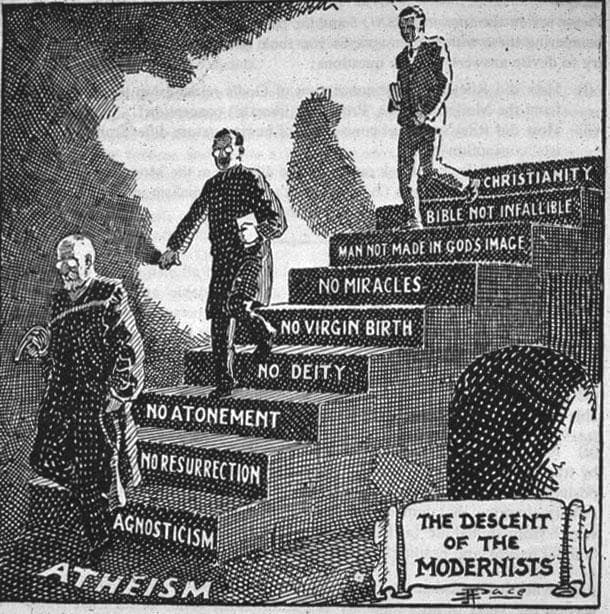

The single most important takeaway from my research involves a famous image reproduced on the front cover of my book.

For Bryan, any form of “theistic evolution”—a term in use since at least 1877 referring to the idea that God used evolution to create living things—was “a way-station on the highway that leads from Christian faith to No-God-Land.”

The cartoon below by Ernest James Pace deftly depicts Bryan’s mental picture, which he shared in a letter to Pace’s editor at the Sunday School Times that is now in the Library of Congress. Bryan wrote that evolution was “the cause of modernism and the progressive elimination of the vital truths of the bible.” He imagined “three well-dressed modernists,” a student, a preacher, and a scientist, descending a staircase with “no stopping place” with “Atheism” at the bottom.

“Descent of the Modernists,” by E. J. Pace, frontispiece from William Jennings Bryan, Seven Questions in Dispute (New York: Revell, 1924). Photograph by Edward B. Davis, from the author’s collection. This cartoon did not appear earlier, although many internet sources have 1922. Because the publisher did not let me preview the back cover of my book prior to publication, I had no opportunity to correct the erroneous date found there.

The more I read modernist publications, the more I was struck by the accuracy of Bryan’s raw analysis of the modernist trajectory, even though many modernists did not make evolution the prime mover behind it (some did).

The strongest confirmation came from an unimpeachable source, philosopher Edwin Arthur Burtt. Reared by evangelical missionaries to China, Burtt studied theology at a modernist stronghold, Union Theological Seminary (New York), and slid progressively away from his parents’ faith. He helped draft the first Humanist Manifesto and signed the second decades later.

While teaching at the University of Chicago in the 1920s, Burtt attended Hyde Park Baptist Church (now Hyde Park Union Church), almost directly adjacent to campus. Mathews and Compton were active members, Mather and his wife had attended during his doctoral studies, and the minister Charles Gilkey (father of the famous theologian Langdon Gilkey) was also a pamphlet author.

When Burtt wrote Religion in an Age of Science (1929), he spoke frankly of his modernist friends: “‘How much can I still believe?’ is the question pathetically asked. … Beginning with two score or more doctrinal articles there ensues a process of elimination and attenuation till today, in liberal circles, the minimum creed seems to have been reduced to three tenets: belief in God, confidence in immortality, and conviction of spiritual uniqueness in Jesus of Nazareth. … Thus the pathetic game of give what must, hold what can, continues.”

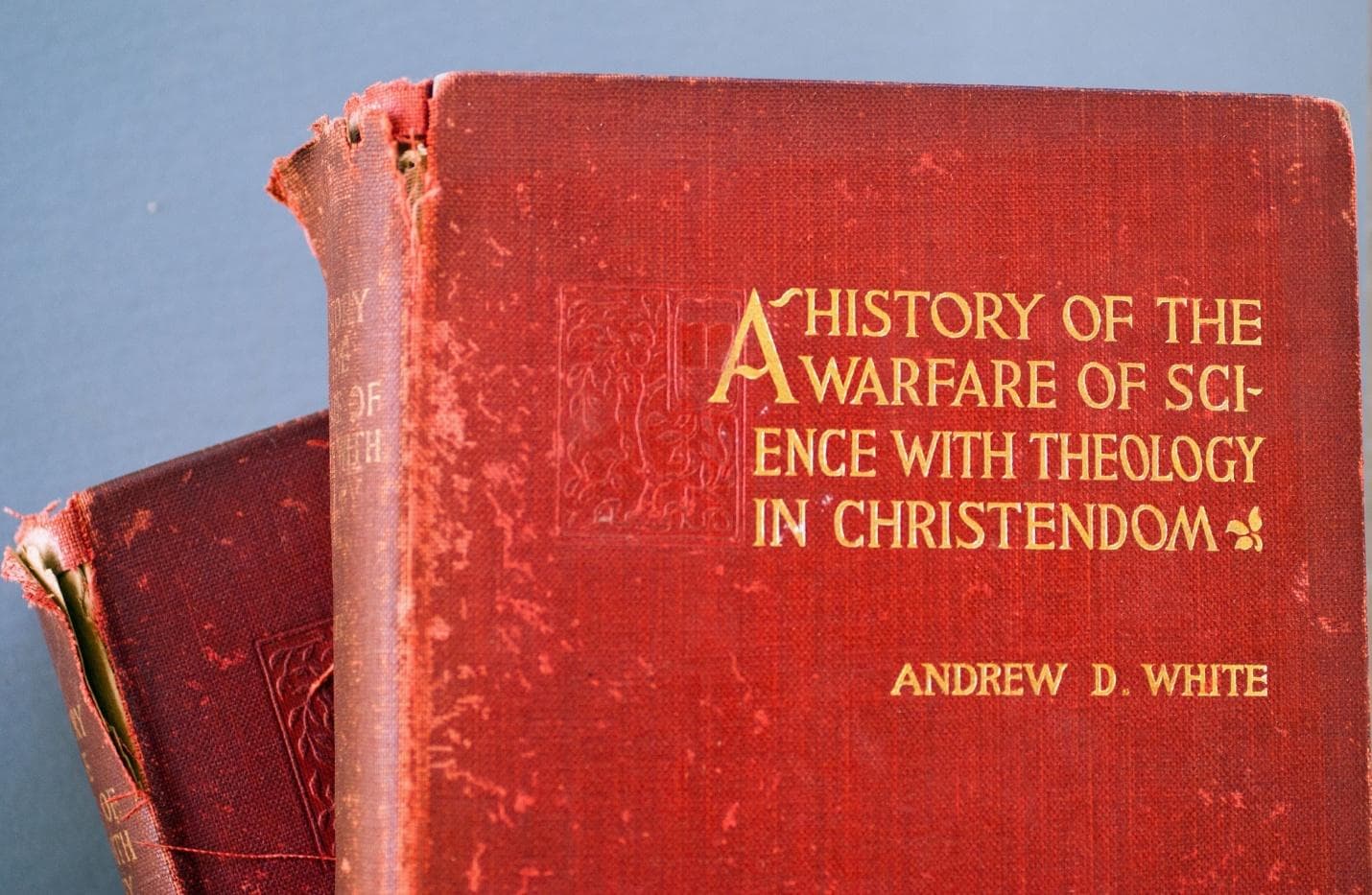

Andrew Dickson White and the Conflict Thesis

Photograph by Edward B. Davis of the second (1897) edition of White’s doorstopper. The first edition’s cover is identical. From the author’s collection.

Burtt and Bryan were spot on. Unbeknownst to them, the bogeyman behind it all was Andrew Dickson White, the first president of Cornell University and an outspoken proponent of the infamous Conflict Thesis of science and religion. The title of his magnum opus says it all: A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896).

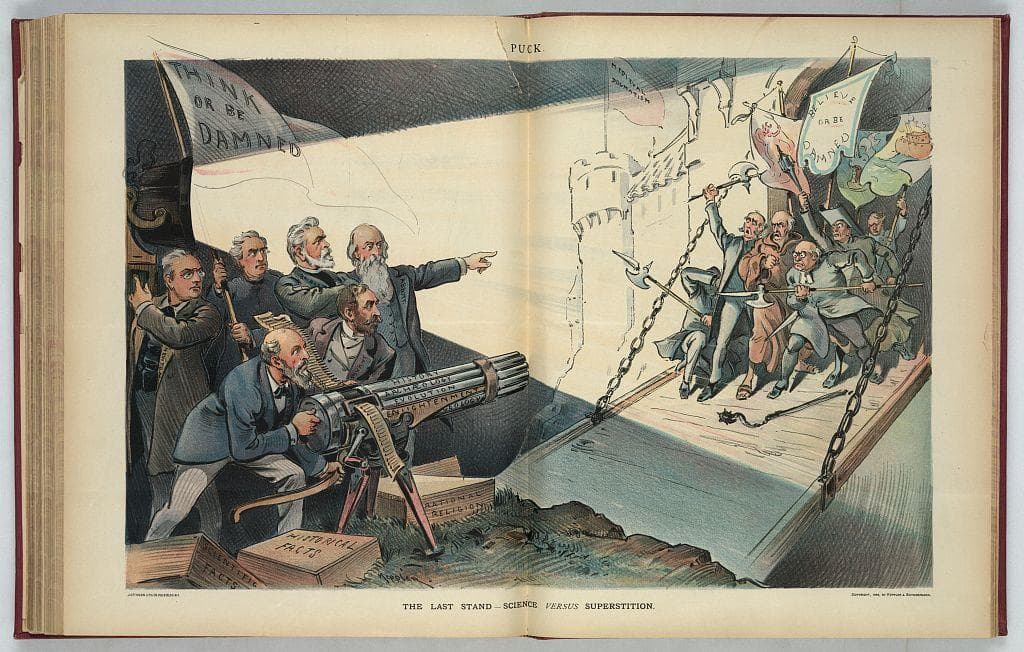

The wonderful image below by Udo Keppler brilliantly displays the close links between American religious liberalism at the turn of the century and White’s historical fable.

The bearded man bent over the Gatling gun even bears some resemblance to White, but he’s the radical Jewish thinker Felix Adler, founder of the Ethical Culture movement and the Ethical Culture School in New York, whose most famous alumnus is probably J. Robert Oppenheimer. Adler’s gun is labeled “History, Archaeology, Evolution, Enlightenment, [and] Geology,” and the boxes of ammunition are labeled “Scientific Facts,” “Historical Facts,” and “Rational Religion.”

His allies, gathered under the banner “Think or be Damned,” are four influential liberal Protestants (left to right): Episcopalian priest Richard Heber Newton, an early proponent of the Social Gospel; theologian Charles Augustus Briggs, expelled by the Presbyterian Church for heresy; Congregationalist theologian Lyman Abbott, a social progressive and an early proponent of theistic evolution; and (feeding rounds into the gun) Unitarian minister Minot Judson Savage.

Their anonymous opponents, emerging from the castle of “Medieval Dogmatism” (terminology taken directly from White), are united under a banner proclaiming, “Believe or be Damned.” The defenders of orthodoxy are immersed in darkness, since we see them only by a searchlight planted firmly on the side of reason.

Chromolithograph by Udo J. Keppler, “The Last Stand—Science Versus Superstition,” centerfold from his magazine, Puck, 19 July 1899. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Keppler’s cartoon underscores an important fact about White and his ideas: unlike the New Atheists of our day, who borrow extensively from White to advance their own agenda in the name of science and reason, White was promoting a very liberal type of religion, a broad and vague theism largely untethered to Christianity, against all forms of traditional Christianity.

The main source of conflict with science in the history of Christendom was what he called “Dogmatic Theology,” a term he used as a pejorative against religious opponents whom he regarded as nothing more than misguided obscurantists fighting a losing battle. He wanted Christian ethics to remain a crucial element in the modern world, and in his view that could happen only if theology got out of the way, preferably quietly and peacefully but as quickly as possible, so that progressive religion could flow on “beneficent and beautiful.”

How the Conflict Thesis Reshaped Protestant Modernist Thinking

Fast forward to 1936, when Mathews published his autobiography, aptly titled New Faith for Old.

In a fascinating chapter called “Religion and Science,” he indicted his life’s work: “It is yet to be seen how far intelligence is consonant with religion.” What follows is pure unadulterated White. “As natural forces replace Divinity and bacteria replace devils, the area of fear within which religions have had control contracts.”

To become credible for modern times, Mathews argued, religion had to recognize what science had done–and what it had done to religion. “Laboratory science did something more than lead to research. It undermined habits of thought and substituted the tentativeness of experiment for authoritative [theological] formulas. True, there were some scientists like Asa Gray who championed Darwinian evolution while holding to the Nicene Creed,” but Mathews did not think Gray was worth emulating.

Why not? “Scientific method had not [yet] reached religious thought. It was only when educational processes had ceased to be controlled by the study of classical literature and grew more contemporary [owing to science], that orthodox theology was felt to be incompatible with intellectual integrity.”

Likewise, the radical modernist theologian Gerald Birney Smith, who taught a correspondence course on modern theology at Mathews’ seminary, recommended White’s book as “a most readable and striking account of the gradual substitution of the empirical method for the method of conformity to authorized doctrine in various realms of thought. It reflects the scientific man’s impatience with the traditional theological ideal.”

White’s two-volume screed appeared just in time to precipitate an intense spiritual crisis in the life of the young man later regarded by Martin Luther King, Jr. (no mean preacher himself) as the greatest preacher of the twentieth century–Fosdick.

Following his first year at Colgate University, Fosdick encountered White’s book, which “finally smashed the whole idea of Biblical inerrancy for me.”

It seemed “unanswerable. Here were the facts, shocking facts about the way the assumed infallibility of the Scriptures had impeded research, deepened and prolonged obscurantism, fed the mania of persecution, and held up the progress of mankind. I no longer believed the old stuff I had been taught. Moreover, I no longer merely doubted it. I rose in indignant revolt against it.”

Like many other modernists, Fosdick lifted the “conflict” picture of White and Draper uncritically from his plate and dutifully swallowed it whole, taking its alleged “facts” as gospel truths to illuminate a new path to righteousness.

One of Fosdick’s countless admirers was Conklin, who as a junior scientist had originally endorsed Asa Gray’s view that Darwinian evolution was compatible with the orthodox creeds. As he grew older, however, Conklin changed his mind.

In language that almost sounds like it was lifted from Pace’s cartoon, he described his own spiritual journey as one that “orthodox friends” might interpret as “descending steps,” leading him further from the traditional Methodist faith of his youth.

“My gradual loss of faith in many orthodox beliefs,” he recalled, “came inevitably with increasing knowledge of nature and growth of a critical sense.”

Significantly, he identified White and his intellectual ally John William Draper as formative influences. As he saw it, they “showed the impossibility of harmonizing many traditional doctrines of theology with the demonstrations of modern science.”

The pamphlets by Conklin and Fosdick, which inaugurated the ”Science and Religion” series in September 1922, both silently incorporated false or misleading information from White to make that very point.

The Long Shadow of the Conflict Thesis

Whether or not White directly influenced their thinking, the early twentieth century modernists effectively embraced the Conflict Thesis as a crucial component of their worldview.

Their profoundly negative attitude toward traditional Christian theology undermined the possibility of having a genuine Christian dialogue with science, rather than just a monologue dominated by science–precisely the result that White sought wholeheartedly to achieve.

Although White denied actual conflict between “religion” and science, he used “science” to drive theology into intellectual disrepute. And he did that, we now know, on the basis of bogus history—despite the salient fact that he was the first president of the American Historical Association.

Modern Echoes: The Conflict Thesis Today

Intellectual descendants of yesterday’s modernists continue to uphold the Conflict Thesis.

And this is ironic: despite their strongly articulated denials of the Conflict Thesis, many contemporary Protestant authors implicitly accept it—that is, they agree with White that traditional theology has proved wholly unable to engage science in fruitful conversation, and so they seek to discard it.

To offer just one obvious example, the late John Shelby Spong, an influential Episcopalian Bishop, believed that science has (somehow) made theism incredible, so he tried to take Christianity “beyond theism.”

Spong’s final lectures at Chautauqua in 2018, based partly on a book by the late Don Cupitt, were apparently nothing more than the Conflict Thesis regurgitated. Neither Spong nor Cupitt knew as much about the history of science as my students, yet their ignorance was used to justify wholly unwarranted theological conclusions.

The New Atheists go even further, proclaiming what I call the “Hard Conflict Thesis.” Proponents want to rid the world entirely of all religion—except their own religion of science, which they naively do not even recognize as religion. Proponents of the softer form, not unlike Spong, want to keep religion and spirituality while removing traditional Christian beliefs root and branch, thus avoiding (in their view) any conflict with science.

To the extent that both groups need the Conflict Thesis to make their narratives work, they have built their castles on historical sand.

Searching for a Middle Way Between Bryan and the Modernists

Is there a middle way between Bryan’s uncompromising rejection of all forms of “theistic evolution” and the modernists’ wholesale rejection of classical theism in the name of “science”?

In the culture war of the 1920s, Protestant thinkers who accepted both evolution and the Nicene Creed, as Gray had done in the 1880s, were thin on the landscape. None of the pamphlet authors qualify, since Pupin was not a Protestant. For the person in the pew, the stark choice seemed to be Bryan or the modernists. Those with more discernment were hard to hear amidst the din of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy.

We still find ourselves today in a culture war involving religion and science, and in one way it’s even more polarized. Young-earth creationism, which had no traction among fundamentalist leaders in 1925, is so dogmatically literalist that even Bryan gets criticized for betraying the Bible.

A list of “compromised” evangelical leaders compiled by Answers in Genesis includes not only Bryan, but a virtual who’s who of evangelical leaders past and present: Billy Graham, Reuben Torrey, James Orr, Charles Spurgeon, Charles Hodge, B. B. Warfield, James Montgomery Boice, Gleason Archer, Bill Bright, Norman Geisler, William Lane Craig, J. P. Moreland, Bruce Waltke, and Tim Keller.

They all made the mistake of interpreting Genesis differently than AiG. They did not “uncompromisingly contend for the literal historical truth of Genesis 1–11, which is absolutely fundamental to all other doctrines in the Bible.” (For more on creationism’s uncompromising tone, see my comments here.)

A New Generation of Scientists and Believers

Nevertheless, in another way the situation has changed fundamentally.

In 1925, there was no one like Francis Collins, an adult convert from atheism to evangelical faith who succeeded the outspoken atheist James Watson as director of the Human Genome Project and later headed the National Institutes of Health.

Nor was there anyone like the late Charles Townes, one of the greatest experimentalists of the last century and a traditional Christian who was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for inventing the maser (ancestor of the laser).

Another Nobel Laureate, physicist William D. Phillips, identifies as an “ordinary” Christian, sings in his church’s gospel choir, believes that science cannot deny miracles and affirms the bodily Resurrection.

Astrophysicist Joan Centrella, a leading expert on general relativity, became a Christian early in her career and led Bible studies for her departmental colleagues.

Distinguished climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe is an active member of an evangelical church in Texas, where her husband Andrew Farley is the head pastor. These names could be multiplied dozens of times.

Two organizations of Christians in STEM fields, the mainly Protestant American Scientific Affiliation and the recently formed Society of Catholic Scientists, have several thousand members, most of them traditional Christians who accept evolution and some of them as accomplished as Compton or Millikan. Neither organization existed in Bryan’s day, when nearly all eminent American scientists whose beliefs are known to me were agnostics, atheists, or modernist Protestants.

The contemporary conversation about religion and science is certainly subtler, broader, and deeper than when John Scopes walked into Rhea County Courthouse.

About the author